Phantom India and the personal journey of Louis Malle

In the fall of 1967, Louis Malle travelled to India to present eight of his films. Fascinated by what he discovered during the trip, he decided to return to India in January 1968 for an undetermined length of time. The small production crew was comprised of his sound recordist Jean-Claude Laureux and director of photography Etienne Becker. His goal was to “change my life and my filmmaking”. Phantom India, the six-hours documentary that resulted from his four-months long journey through India can be described as a travel log. His only guides were his intuition and his curiosity.

By 1967, the French film director found himself in an artistic impasse. This happens to many young directors: their careers flourish fast, and they are given more work than they can chew, losing their artistic insight in the process. At age 36, Malle had already directed eight feature films and had found success on the stage of international cinema. Yet something was missing, and he knew it. He’d made his most personal and radical film, Le Feu Follet, in 1963, a film he referred to as a “personal self-exorcism” The two films that followed, Viva Maria!(1965) and Le Voleur (1967) were opportunities for Malle to work with stars such as Jean-Paul Belmondo and Brigitte Bardot, and bigger means than he was used to. However, the films give the sense that Malle was trying to blend in with the international film community instead of embracing the versatile curiosity that had come to define him at a young age. His invitation to India came at a fortunate time in his career which was in need of reinvention.

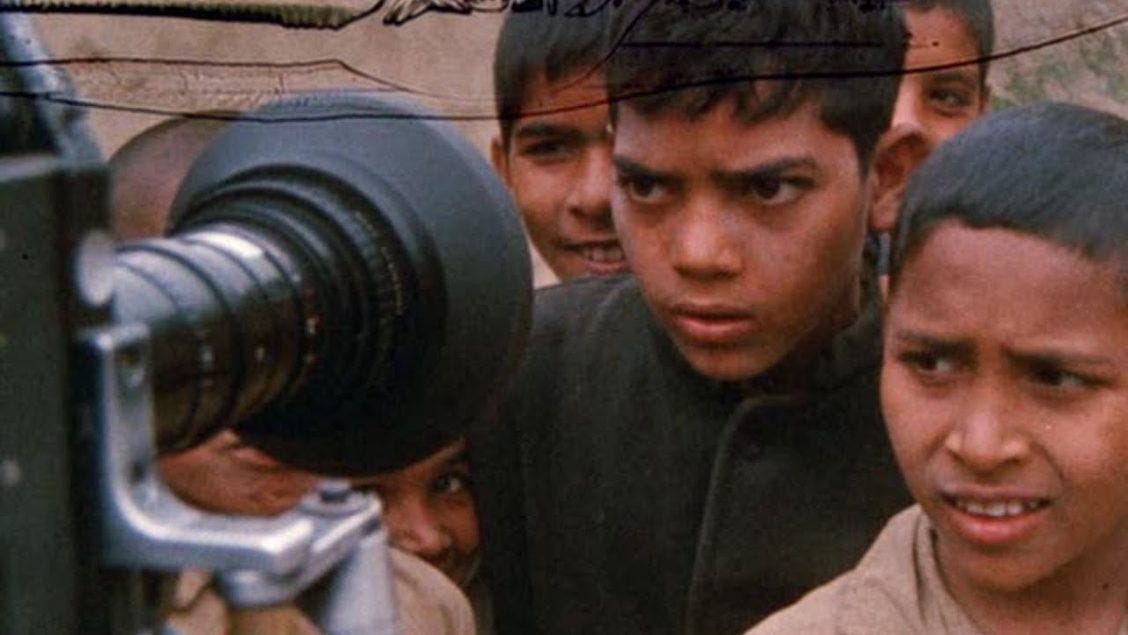

Phantom India gives the impression of someone falling in love: thunderstruck, Malle engaged with the country with insatiable curiosity, using his own perspective to understand it. The more Malle films of the country, the less he tries to understand it, giving way to being in the present moment while filming, and in turn showing confidence in what he chooses to observe. Malle is conscious of the fact that being a foreigner with a camera makes him as much an observer as a subject of observation. In the first episode of the series, the crew arrives in a village and are surrounded by curious children. Most filmmakers would decide to edit that part out of their film as it turns the camera’s gaze unto themselves. Malle keeps it in the film and makes the image the illustration of his endeavor in India. He realized that in his search for something real, he had to include these interactions: “I understood quickly that these eyes directed at the camera were disturbing and true, we couldn’t fake not being the intruders. We decided to keep working in that manner.”

What struck me the most from watching the hypnotic film was how intimate it felt. The camera is so subjective it gives the impression of first-person point of view in a way I had not seen in a documentary before. We see what Louis sees, to the point where I was wondering whether Etienne Becker, the cinematographer, ever held the camera himself. The narration told by Louis himself furthers this impression of intimacy. We are right there with him, witnessing what he sees through the camera’s lens in real time. After finishing the series, I realized that the game he played as narrator and director was a deconstruction of the idea of objectivity. He realizes that his documentary cannot be an objective accounting of India, thus assuming the subjectivity of his film. In the end, his objectivity comes from assuming his subjectivity.

When Malle arrived with his crew in India, he couldn’t help himself but make comparisons to scenes relevant to his western origins. For example, he catches himself witnessing the spectacle of vultures eating a cow: “When I see this scene today, I realize that we reacted within the pattern of our culture […] To us it was a tragedy. To the Indian man who was guiding us, it was a banal scene, the image of life and death, their steady alternance. There was nothing to film, nothing extraordinary.”

Malle lets go of narrative, choosing instead to improvise and embracing the unpredictability of his subject. It may sound contradictory for a documentary film, however what Malle achieves is a film deprived of any objectivity. As he said in a 1974 interview: “The experience changed me, it made me see things differently and forced me to reconsider who I was. It didn’t teach me much about India, but it taught me a lot about myself.”

“You can’t escape yourself when making a film.” Louis Malle declares in the first episode of Phantom of India. Six hours later, I felt like I knew him much more intimately than after watching any of his other films. His curiosity led him to India in search of something more meaningful in his own life and art; judging from the work that followed, the impact of the months he spent in India was tremendous. The two feature film he made after returning to France, Murmur of the Heart (1971) and Lacombe Lucien (1974) are amongst his best and the sign of a strong shift in his filmmaking. Louis Malle came back from India more confident, uncompromising, and personal in his filmmaking.

Paul Malle